Husband: “What are you reading?”

Me: “A biography of Karen Carpenter.”

Husband: “What’s interesting about Karen Carpenter?”

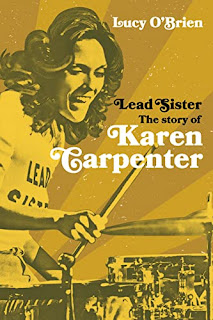

It’s true – and it comes up many times in Lucy O’Brien’s new book Lead Sister – that Karen Carpenter had an image problem. Basically, she wasn’t very rock’n’roll.

The first time I heard the Carpenters, it was a record owned by my friend’s parents. That says it all, really. But I still loved the song (“Close To You”). They did get playlisted on Radio 1, too, and I remember waiting eagerly for “Goodbye To Love” to come round again. And I still love “Yesterday Once More”, which feels increasingly meta with every passing decade.

Yes, they were good. But they weren’t hip. After all, the story of the Carpenters’ music starts with church choirs and a love of jazz. Sure, they were massive in the pop charts but they never threw off their square image. And when Karen tried to do something different with a solo album, the record company rejected it.

On the other hand, Karen was a drummer and, we are told, a really good one. That gives her a bit of an edge, surely.

Name as many female drummers as you can. This could be a good Pointless question. There are probably more than you thought, but they are still very much a minority. How many people out of the hundred would have remembered Karen Carpenter?

Lucy O’Brien, as you’d expect from the author of She Bop, tells Karen’s story from a feminist perspective. That means putting in the in the context of the 1970s music industry – after the heyday of female torch singers but before the rise of female instrumentalists, meaning that, in career terms, Karen Carpenter was in the wrong place at the wrong time. And was working at a time when pop wasn’t taken seriously as an art form, because it was for girls.

So, does being a drummer make Karen Carpenter a feminist icon? Or does being fucked up by her family and the music business make her a feminist victim?

The book argues for both, but the latter is what comes across most strongly while you’re reading. The narrative trajectory towards Karen’s death from anorexia reminds me of Careless Love, the second volume of Peter Guralnick’s Presley biography. As in that story, the self-destructiveness has an inevitable momentum towards tragedy.

Like the Presley book, the story is comprehensively, almost academically, researched and is told mostly through other people’s words. In Lead Sister, each chapter has an epigraph taken from a published interview with Karen. Otherwise, the words are other people’s: colleagues, lovers and friends.

And of course, there are also quotes from Richard, the older brother who made the career decisions – including the one to take Karen away from the drums and recast her as the typical girl singer. And the person who was seen by their mother as the most musically talented and the most important.

It’s quite hard for a feminist author to deal with a story where the mother is the problem, but that does seem to be the case here. It appears that the whole family was dysfunctional, though. Nothing unusual about that, but when you add those pressures to the pressures put on women by the music industry, it’s a recipe for disaster.

There is, though, more to Karen than that, and O’Brien aims to reframe the story. The Karen described by those who cared for her was a “tomboy”, happier in jeans than the frumpy dresses she wore on stage. She was funny, and fun to be with. Her personality attracted friends and lovers. She had her own musical ideas, credited as co-producer on Carpenters’ records and heading for new directions with her solo work. And she was a serious musician, dedicated to the drumkit. Finally, O’Brien focuses on Karen’s musical legacy, arguing for a re-evaluation of her work.

What’s interesting about Karen Carpenter? Quite a lot, it turns out.

No comments:

Post a Comment