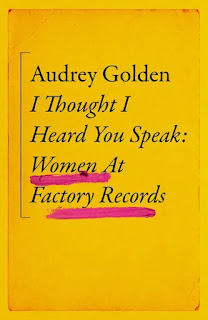

We all know that the history of popular music – like the history of most things – is a tale told by men. I’ve also read enough books about Factory Records and the Hacienda to know that their history has largely been told by men, too. This is the antidote.

Audrey Golden interviewed dozens of women: the ‘Cast of Characters’ at the beginning of the book covers four pages. All worked for Factory and/or the Haçiienda in one capacity or other; in many cases, in several. Many did the behind-the-scenes admin work, many were creatives; again, in many cases, they were both.

There are some that many readers will have heard of: Gina Birch (The Raincoats), Cath Carroll (Miaow/NME), Gillian Gilbert (New Order), Brix Smith (The Fall), Linder Sterling (Ludus). There are others you will know about if you are closer to the Manchester scene than I was, while others were strictly backroom women and, up to now, unsung.

The book is an oral history, which means it is many voices, many telling the same stories, each telling them differently because that’s the nature of memory.

It’s not completely unfiltered – the words are organised and structured so that each chapter covers a different aspect of the story/ies – but there’s very little authorial commentary (just a short introduction to each chapter to put it into context). There doesn’t need to be. The women’s voices say what needs to be said.

DJ Paulette is one of those included, and has also written the foreword. She has some strong words about what she calls “the mansplaining of history”: “In the last twenty years, more than a dozen books have been published on the Factory Records story yet none among them has ever given the women their flowers.”

A man, she says, will write about “the loud, active parts of the machinery he immediately sees”, not acknowledging that “women have regularly saved the day and made others shine.”

Yes, that old thing about “women’s work”: invisible, but making the world turn. It runs through every part of the book.

The women in these stories may not be the “24-hour party people” we’ve been told about before. It sounds as if most of them know how to party, but they also know how to make the party happen, and pick up the pieces the next day.

The story begins with the truth that, in the words of Martine McDonagh “the women running Factory didn’t get the credit they deserved.” And in this new version of the story, it is women running the record label from the start. But being organised and capable is never as glamorous as running around being visionary and maverick and making expensive mistakes.

What’s great about this book is that the women are telling their own stories but they are also giving credit to the other women. According to their colleagues, Lindsay Reade (then Wilson) “was absolutely brilliant”, Tina Simmons “made it into a proper business”, Lesley Gilbert “did everything”.

That’s about the beginning of the label. It’s the same when we get to the Haçienda. Ellie Gray “was so significant in the early formation of the Hacienda” and “really knew her stuff”. Penny Henrry is “one of the forgotten women of Factory”.

Penny Henry is one of those who is explicit about what that feels like. Peter Hook, she says, “never bothered to speak to me about his book”. And the film 24 Hour Party People, she says, suggested that “if the facts aren’t that interesting, just make it up.”

Actually the facts are interesting and there’s lots of them. There are the well known ones like the Smiths’ first gig and the famous Madonna appearance, and less known ones like the fashion, art and performance events that made the Haçienda part of Manchester’s wider cultural (and gay/lesbian) scene.

There’s no myth-making but there are lots of great stories because, as we already know, there was plenty of drama during those years. We’ve heard some of it before but not told in this way, or from this perspective.

While the women here make it quite clear that history, and those who tell it, has undervalued them, many describe a family atmosphere at Factory and say that it didn’t feel as sexist as other parts of the business that they encountered: many say that at the time they felt equal.

The book has a point to make but it doesn’t have an axe to grind. For many, too, the Manchester experience was life-changing in terms of careers.

As the story progresses from the early days of the label, you hear about the rise and fall of the club – “a shambles” at the start until the women stepped in (and the ending wasn’t much better).

Nicky Crewe was in the box office on the first night: “You see it mythologised, and I was there, but in the written history, the mythologised history, I’m not there.”

Bev Bytheway echoes this: “We all played roles, and I still don’t think that’s ever been looked into. The story never changes. It’s the same lead characters every time.”

This time, the lead characters are different. There is a record now. It will go down in history, and as history. That matters.

No comments:

Post a Comment